Occasionally, we get the much appreciated opportunity of giving a talk in a class. It’s important to us to talk to people about our ideas and our work, to make sure we’re not operating in a vacuum. In particular, we’re really interested in what students are thinking about — what they’re interested in, what they’re struggling with, and how that reflects on the design and tech industries that we belong to. What work can we be proud of that’s getting students excited about a future in our industry, and what messages are we sending that we should be careful about?

The AI question has been coming up in our discussions. Some students are excited about it, some are wary, many are curious about how we think about it in our practice and our work.

The short answer is that we don’t use generative AI, and we don’t have any plans to do so. We’re a small company, so with our limited amount of time and resources, we really value focusing on work that get us excited to show up every day, and generative AI isn’t that kind of work. There’s a plethora of arguments to lay out about the ethical and environmental ramifications of this technology, but a lot of what we’ve been sharing in response to students has been, in a smaller way, about the kind of work culture and interpersonal culture we like to foster.

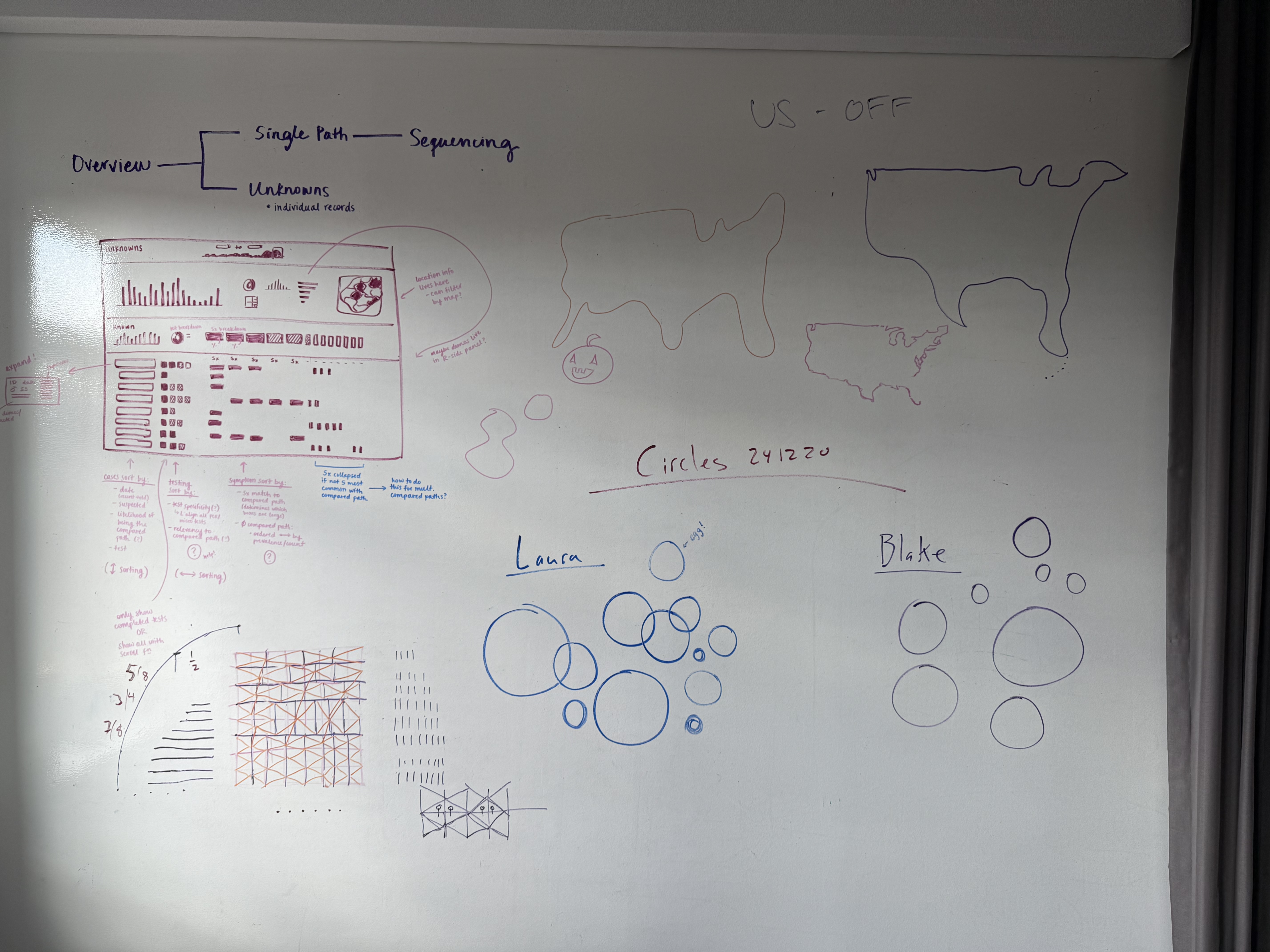

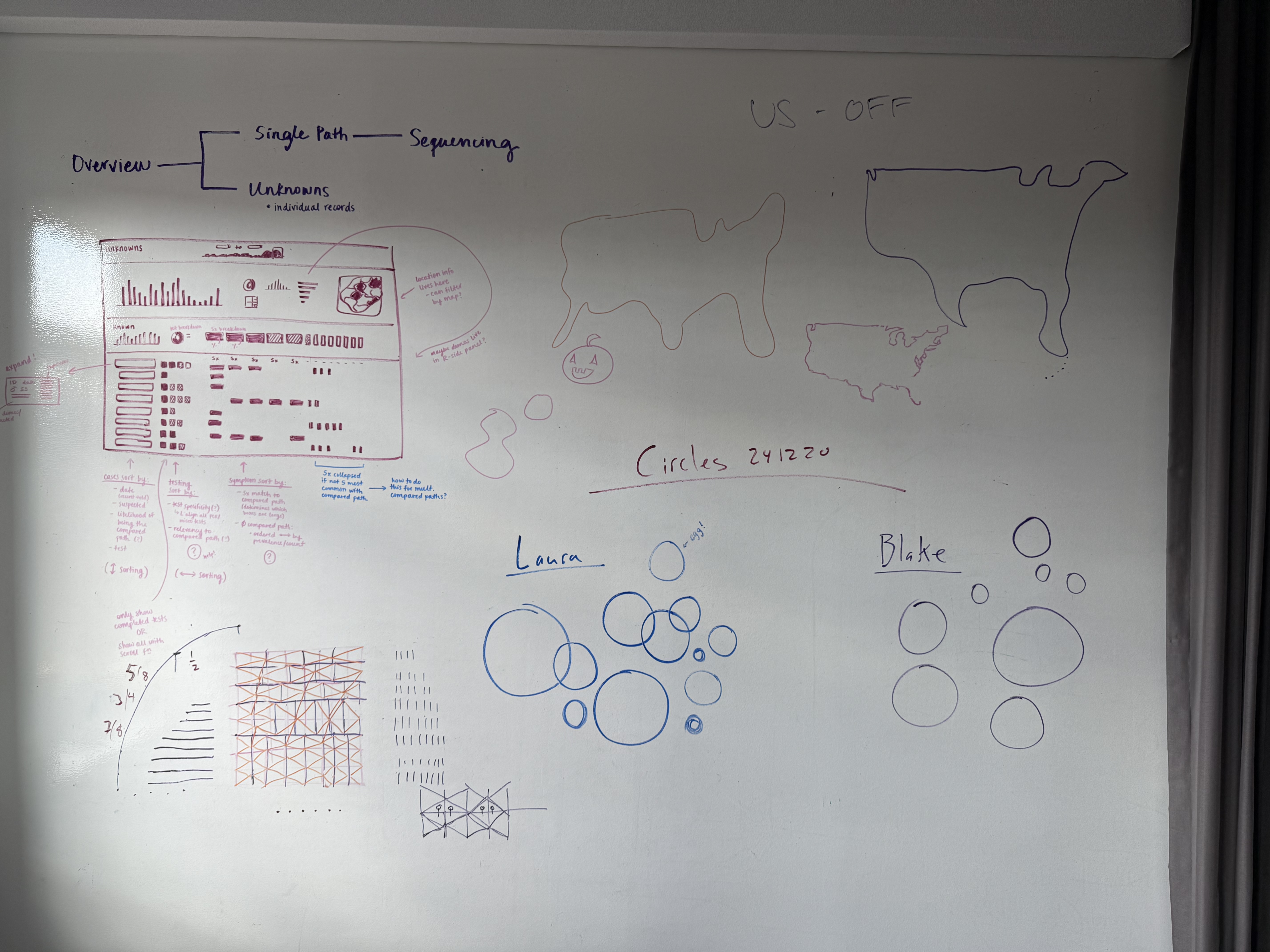

A huge part of the way we work is how we talk and collaborate with each other. The most crucial part of the process is sitting in a room (whether that’s in person or virtual) and being able to articulate and respond to each other’s ideas. Making and sharing high-fidelity sketches or prototypes too early on in the process can distract from more important questions at that point. Instead, we talk, gesture, and draw rough sketches on the whiteboard, which is often all that’s needed to get abstract ideas out of people’s heads and across to each other. We draw from each other’s lived expertise to get a sense of the complexity and feasibility of different ideas. If we don’t know if something’s going to work in practice, we practice rapid prototyping — meaning that we make rough interactive prototypes, but share and critique them frequently to make sure we can change course whenever necessary.

Another part of the collaboration practice is how we grow through internal learning and mentoring. We learn so much from discussing problems and solutions with each other. Sure, there are technical skills you can probably learn on your own, but there are many other problems that are more about working as part of a living and growing team with institutional knowledge and memory. When a newer team member is faced with a problem, it’s incredibly valuable to be able to talk with a more tenured team member about how similar problems were solved in past projects. That exchange helps the newer team member learn how to solve a problem, but also helps everyone keep that institutional memory alive and growing — sometimes we’re able to reflect on those past solutions and come up with better, more modern solutions, too.

Aside from process and practice, AI frustrates us in another way that’s more personal and specific to our purpose as a studio. Much of AI these days is a black box — type a message in and get something illusory out, with no way to predict what that output will be or even to trust it at all. Our bread and butter is information design: the pervasive challenge, in every domain, of taking a complex idea or story and distilling it into a clear, intuitive, beautiful format. If we’re making tools for experts, we want to respect their expertise and time, and craft a product that helps them with the difficult parts of their job, not another kludge that they’re burdened to spend time wrestling with and debugging. We want to make thoughtful products, where it’s clear that someone has spent time thinking about the hard parts of a task and has invested the time and effort into making that a smooth process. If we’ve found ourselves in a hole where the black box model of solving a complex information problem is the only solution, we’re not doing our job as information designers, and we need to go back to the drawing board.

Because we work in data, though, it’s also worth emphasizing that the term “AI” can often be painted with a broad brush these days. We aren’t excited about generative AI, but there’s still a very meaningful place for tried-and-true techniques like modeling, machine learning, and natural language processing. We’ve dabbled in different techniques whenever they have been appropriate for different projects. We did briefly experiment with generative AI in one project, to be fair — we just weren’t convinced.

There have always been interesting and worthwhile challenges to tackle, big and small, and that continues to be true for us outside of the current trend of generative AI. We’re dedicated to our Sentinel work with the Sabeti Lab for thinking about large-scale pandemic prevention, where many of the challenges are logistical — how do you make tools that help people collaborate among existing workflows and limited resources? We’re in our second year of Rowboat being available publicly as a tool for data exploration. Even with our effort to distill years of experience into tools like Rowboat, there are so many aspects of data exploration work that still need to be improved, and that’s the work that gets us excited to show up every day.

Ultimately, we can’t make a grand proclamation about what the future of our work looks like. But right now, we’re privileged to be in a position where we can stand by our expertise and invest in a future we believe in.

We’d love to hear what you’re working on, what you’re curious about, and what messy data problems we can help you solve. Drop us a line at hello@fathom.info, or you can subscribe to our newsletter for updates.